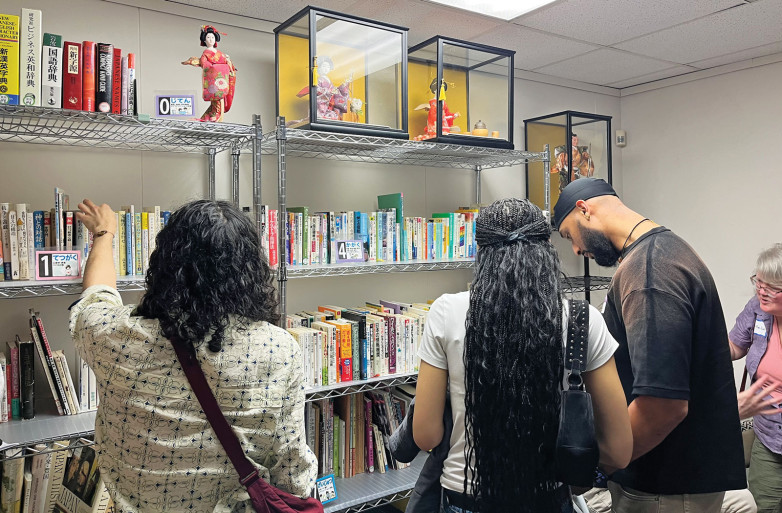

The books “serve as a bridge between generations, helping elders stay connected to their roots while allowing younger generations to discover and understand their cultural heritage,” said Shizuka Durgins, founder and president of the Cha-Ami Japanese Cultural Center. The nonprofit organization aims to “promote an inclusive and diverse environment where people can come together and share their stories and experiences.” It now houses approximately 2,000 of Breckenridge’s books.

“She wanted to have a place for Japanese women to gather, share their love of books, and support each other,” said Marnie Jorenby, a senior lecturer of Japanese at the University of Minnesota. Jorenby is ensuring Breckenridge’s wish continues to be fulfilled by converting a barn on her property into a repository for 25,000 of Breckenridge’s books and a communal meeting place to gather and share stories. “Wandering through a library,” Jorenby said, “puts one in front of all sorts of books. … A library provides fellowship.”

Durgins concurs. “Through these books, we hope to offer the community a doorway into Japanese culture, language, and everyday life,” she said. “We want people of all backgrounds to discover not just stories but also a deeper understanding of Japan’s traditions and values.”

From copying books by hand as a young girl, Breckenridge went on to facilitate her own library in Minneapolis, a place that brought the city’s multilingual communities together. She once told Jorenby, “The door of a library should always be open.”

And it will be. And not just one library, but two for anyone to learn—manabu.